By Emily Ball Cicchini, Executive Director

The statistics about the struggle to achieve full literacy in America are startling and alarming: 14% of Americans are illiterate, with little change over the past decade, and 21% of adults can’t read above a fifth-grade level. Numerous studies connect lack of reading skills to negative life outcomes such as poverty and crime. Why is it so hard for the United States to catch up with Norway, Slovakia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, where the literacy rate percentage is already at or near 100? Recent studies about the literate brain might hold some answers.

Where Does Reading Ability Come From?

For as long as people have communicated in writing, there have been arguments and practices about how to best teach children and adults to read. While linguists and developmental psychologists differ on the origins and functions of language, it seems clear that talking and listening can occur naturally as a child grows, but reading and writing are systems of man-made code. This means that a child must be taught to read and write in the language of their community.

Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century

Tufts University researcher Maryanne Wolf and her colleague Stephanie Gottwald have been studying reading and the brain for many years. Their recent book, Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century (Oxford, 2016), argues that the problem, as well as the solution, begins at home when a child is first born. They describe the additive effects of parents reading aloud to children: Not only does the repetitive exposure to sounds, words, letters, and concepts develop the neurological paths that enable later independent reading, but the intimate bond that develops through reading also helps the child associate language with comfort and love.

What Happens in a “Reading Brain”?

Wolf dives deeper into what happens in the brain when humans become fluent readers and delights in the generative act of deep reading. This is the kind of long, sustained reading that people do for pleasure or for advanced study. When we are immersed in a world of written words, our brain makes novel connections between what we are reading and our past experiences, creating new perceptions, definitions, associations, and knowledge in the process. Like many others, she is concerned that digital devices are changing, and perhaps endangering, this type of generative “reading brain,” leading to a fear that humans could ultimately lose the capacity to learn and create.

The Emergence of Two Literacies

For Wolf and many parents, the most dangerous aspect of the digital age is the constant distraction of an abundance of mobile screens. Frequently changing images and floods of short text messages disrupt the flow of attention, and engage instinctual “fight of flight” responses that add to stress and a superficial perspective of the world. However, Wolf observes that there are increasingly two types of student readers: 1) those who are high performing on print, but low on digital, and 2) those who are high-performing on digital, but low on print. For example, some children who are reluctant or struggling readers in print seem to blossom when given a tablet device, where they can read and absorb information in a more categorical, non-linear fashion. Her conclusion: perhaps we may be seeing the emergence of two different types of “reading brains” — both with uniquely constructive attributes.

What Would “New Reading” Look Like?

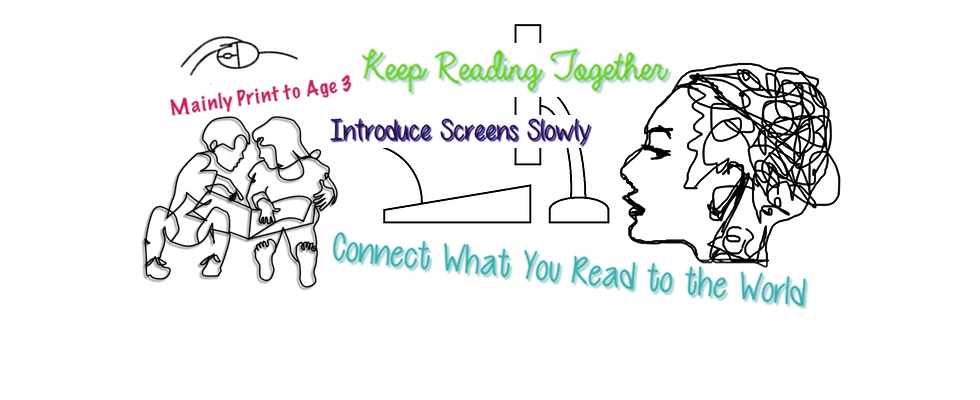

While Wolf’s book stops short of setting an agenda for 21st Century reading instruction, she hints at where she and her colleagues, including psychologists, neurologists, and leaders in the public service sector, might be headed. While she is nervous about the potential dangers of the misuse of digital communication (a rabbit hole of distractions), she is excited about its potential to get words and language and ideas to communities that have historically been isolated and marginalized from access to knowledge of any kind. Without going into detail, she hints at a developmental strategy that might involve very close print reading in the home for the very youngest of children (perhaps from birth to age 3), augmented with controlled exposure to digital reading with guidance in early childhood (perhaps from age 3 to 8), and more complex independent digital reading choices for older readers, without losing the print basis (from ages 8-12).

What Parents and Teachers Can Do Today

It seems intuitive, but the formal research behind these methods still needs to be completed. Research takes time, and we’re living at a pace where technological innovations are moving faster and faster out into the marketplace, making it hard for scientists to keep up. And yet, paying attention to what is happening with our children is one of the most important activities we can do. Here is where empathy, intuition, and the art of sharing reading comes into play. Parents should notice when their children are tuning out the world in favor of flashing images and sound on their screens, and help them instead find high-quality content with well-written prose and well-designed pictures, sound, and interactive features. They also can give children a wide choice of print books and encourage deep reading with a quiet and sustained time that demands their full attention. It’s part of our jobs as responsible adults to not let technology win the battle for our children’s values, understanding, and attention.

How BookSpring Plays a Part

This is the role that a small, community-based organization such as BookSpring can play. We can be the gathering place where parents, teachers, doctors, and anyone who cares about children and the future of our community can come together to share the importance of reading — in any format. We can share resources, such as Epic, the Netflix-like subscription digital book service that is free to teachers, as well as recommendations for the best new board and chapter books. And we will continue to distribute free books to own throughout our 100-mile service area through our healthcare, education, and community partners. Book ownership counts and helps create a tangible space to make reading both a priority and a joy.

While we may not be able to change the literacy rates across all of America, we are aiming to change the literacy rate right here in Central Texas. And, to riff off a well-known local tagline: What young readers we start here, may very well change the world!

Note: Links to the sources in this article are purely informational and BookSpring receives no compensation for our recommendations or referrals.